The Enduring Appeal of the Arabic Language and Script

Sean Hopwood, MBA is founder and President of Day Translations, Inc., an online translation and localization services provider, dedicated to the improvement of global communications. You can visit their website if you need Arabic translation services.

What is it that makes Arabic so special? Is it the way the cursive dashes and hooks beneath the staccato accents? Or that it’s written from right to left like Hebrew instead of left to right like the romance languages? Perhaps it’s the phonetic precision, or the rich cultural heritage that the calligraphy conjures up.

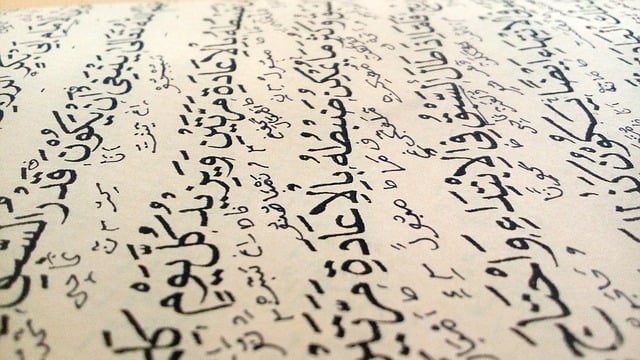

Just a glimpse of Arabic script can take you back to the enchanting days of sandstorms and sheikhs. It calls to mind gilded, handwritten Qur’ans, or the literature and sufi mystic poetry of medieval Islam’s golden age.

Table of Contents

Photo via Pixabay

What Makes Arabic So Enchanting?

Arabic is special. There’s no doubt about that. It’s the official language of almost 30 nations worldwide, and one of only six official languages of the United Nations. And 420 million speakers on earth make Arabic the world’s fifth most widely spoken language, after English, Spanish, Mandarin and Hindustani.

Arabic comes from the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family. It was born in iron age Mesopotamia and the Arabian peninsula. A multitude of regional varieties and dialects of Arabic are flourishing all over the middle east and north Africa. Muslim devouts in non-Arabic speaking parts of the world learn it as a foreign language for use in prayer and religious study. The Arabic language, therefore, is a major component of our world’s cultural heritage.

Photo by Walters Art Museum Illuminated Manuscripts via Flickr

Arabic script, the writing system that brings visual form to the Arabic language, is special as well. The 28 letter cursive system, called an abjad, is used for writing not only Arabic, but Farsi, Urdu, Central Kurdish, and the Mandinka language of West Africa, to name only a few.

The abjad isn’t an alphabet proper, as each letter denotes a consonant sound. A true abjad has no vowels.

For the ‘aleph beta’ writing system, the grandfather of the alphabet you’re reading in right now, ninth century Greeks adapted the Phoenician writing system to include symbols that represented different vowel sounds. Aleph beta, the first two letters of the Phoenician writing system, meant ‘ox house.’

Arabic script went in a different direction, and like Hebrew, used letterforms only for consonant sounds. Most modern abjads, however, do contain a few symbols for long or double vowels. The vowel sounds are usually expressed as dots, dashes and loops either above or below the consonant forms. The A-B-J-D sounds of the first four letters give it the name abjad, similar to how we got the word ‘alphabet.’ Modern varieties that contain limited vowel sound indicators are called ‘impure abjads.’

After the modern Latin alphabet (which comes from the Phoenician one), Arabic is the second most widely used writing system in the world.

Just like the Latin alphabet is used to write English, French, Spanish, even Vietnamese and many other languages, Arabic script is used to write a multitude of languages as well. In fact, until the 16th century, people were even using Arabic script to write Spanish. The transcription of European languages in Arabic is called Aljamiado.

There are also many other writing systems, such as Persian script, that are based on Arabic script. Persian script shares many features in common with Arabic script, but it has a few letters not included in Arabic, and a different personality to its letter forms. Another example is the Ottoman Turkish alphabet, which was in use until the 1920s when the modern, Latin-based Turkish replaced it.

The Birth of Arabic Script

Kufic is the oldest Arabic script. It’s more angular than modern Arabic, and didn’t have the accents marks or dots. It developed in 7th century Iraq, in the Lower Mesopotamian city of Kufa. Its older ancestor, Nabataean, more closely resembles Aramaic and Hebrew. The Nabataean abjad can still be seen inscribed on the ruins of Petra in Jordan.

Around the 10th century, a cursive Arabic script called naskh emerged. It was pioneered by the esteemed court official and calligrapher Abu ‘Ali Muhammad ibn ‘Ali ibn Muqla al-Shirazi, also known more simply as Ibn Muqla. As a more lyrical version of Arabic script, naskh script would develop into what we know as modern Arabic today.

The widening global use of Arabic corresponded to the spread of Islam as a major world religion. By the 14th century, other forms of Arabic cursive were developing in places like Turkey, Persia and even China. Sini, a Chinese form of Arabic script, dates from the Tang dynasty when Islam arrived in China. It phonetically translates Chinese sounds into Arabic script, and is still in use today.

The Practice of Arabic Calligraphy

Writing in Arabic script is a time-honored art form. Elaborate illuminated manuscripts adorn the history of Islamic writing. As paper replaced papyrus and parchment, the Muslim world was filling volume after volume of paper books with knowledge while Europe was still clinging to a few moldy texts to preserve culture and heritage. Antiquarian handwritten Qur’ans with gilded covers and colorful inks are available to view in museums all over the world. They speak to the rich tradition of Islam, and the central role that Arabic calligraphy plays in it.

Some of the most popular motifs for Arabic calligraphy are the Bismillah and the Shahada. A Bismillah is a rendition of the phrase b-ismi-llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīmi, or “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.” This is a common phrase in prayer and other aspects of Muslim practice. Calligraphic forms of the phrase often appear as geometric patterns, or occasionally as pictograms like a fruiting branch or an animal. The modern Unicode version of the Bismillah is U+FDFD: ﷽

A Shahada is a testimonial or declaration of belief (e.g. “There is no god but God. Muhammad is the messenger of God.”) This phrase appears frequently in historical Arabic calligraphy, but is not quite as ubiquitous as the Bismillah.

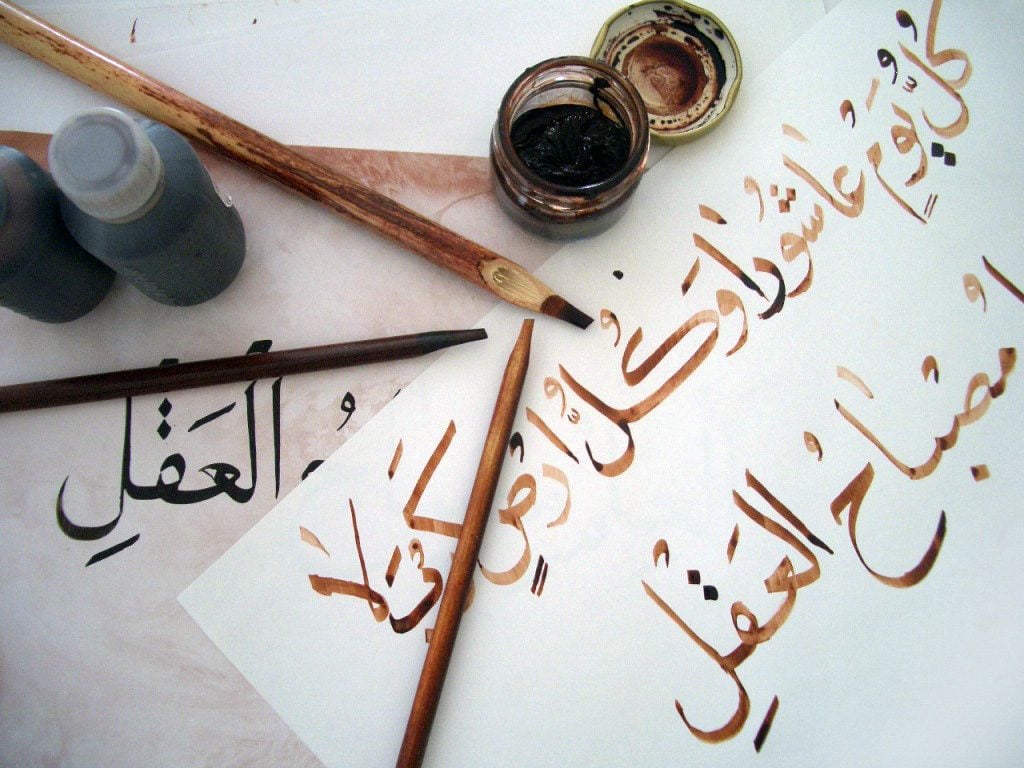

Arabic calligraphy traditionally uses a qalam, a simple pen made from a reed, as compared to a Chinese bamboo brush or a European feather quill. For larger letter forms, there’s the celi pen. This uses a broad hardwood nib with drilled reservoirs for a wider stroke. A Javanese thorngrass is popular for smaller, tighter script.

Photo of a Qalam by Aieman Khimji via Wikimedia

Contemporary calligraphers also practice with felt tipped markers, like a Sharpie that has a wedge shaped tip, or a very broad, brush-like tool called a kelani.

Inks for Arabic calligraphy come in a variety of colors. Many are made to have dynamic variations corresponding to stroke speed. For example, a short or slow stroke will produce a dark, nearly black color, but a quick long stroke in the same ink will appear as a translucent red. When these strokes overlap, there’s an interplay between their transparency as well that creates layers. In the hands of a good calligrapher, the effects can be breathtaking.

Learning Arabic Today

Learning the Arabic language and script is unlike most other language learning you can do. Readers of Arabic recognize words differently than those reading other languages. Usually, when we learn a language, our left and right brains are both engaged, for the technical and creative aspects, respectively. With Arabic, however, the intricacies are so complex that the right brain doesn’t even engage. Learning Arabic is an almost exclusively left-brain endeavor.

With all that technical complexity comes a remarkable level of precision. Arabic is renowned for the way its letters precisely correspond to the sounds they represent. You won’t find those murky gray areas like the nine different pronunciations of ‘-ough’ in English. In Arabic, the way it is written is the way it is pronounced.

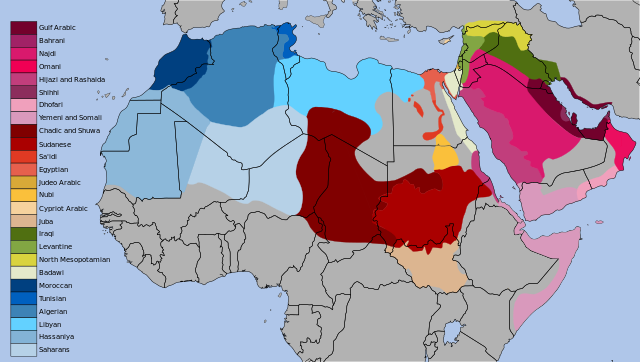

Different Arabic varieties in the Arab World via Wikipedia

Arabic is an extremely useful language. Learning it will open the doors to a vast portion of the world, as it’s the official language (or an official language) of the following countries:

– Algeria

– Bahrain

– Chad

– Comoros

– Djibouti

– Egypt

– Eritrea

– Iraq

– Israel

– Jordan

– Kuwait

– Lebanon

– Libya

– Malta

– Mauritania

– Morocco

– Oman

– Palestine

– Qatar

– Saudi Arabia

– Somalia

– Sudan

– Syria

– Tanzania

– Tunisia

– United Arab Emirates

– Yemen

– Western Sahara

In 1974, the UN adopted Arabic as one of only six of its official languages, meaning Arabic is used as a touchstone for international cooperation and understanding. The Arabic speaking world is a powerhouse in business and global politics. Consequently, Arabic is one of the most in-demand languages for over the phone interpretation and other translation services. Studying Arabic today connects you not only to a rich and vivid history, but to a thriving present.

Whether your interest in Arabic is aesthetic, spiritual, historical, political or commercial, the captivating quality of the language cannot be overstated. So if you’re learning Arabic, don’t be daunted. It may not be the easiest language or writing system to pursue, but the rewards are deep and complex.

The Arabic script and language hold prestigious positions in the halls of civilization’s development. Since the dawn of Kufic script to the modern Unicode Bismillah, from medieval Qur’ans to the interpreters of the UN, the importance of Arabic shows no signs of waning. It has always contained and continues to contain a rich portion of world knowledge and culture.